Robert D. Kaplan comments on what it takes to earn the highest award the military can bestow—and why the public fails to appreciate its worth

No Greater Honor

Over the decades, the Medal of Honor—the highest award for valor—has evolved into the U.S. military equivalent of sainthood. Only eight Medals of Honor have been awarded since the Vietnam War, all posthumously. “You don’t have to die to win it, but it helps,” says Army Colonel Thomas P. Smith. A West Point graduate from the Bronx, Smith has a unique perspective. He was a battalion commander in Iraq when one of his men performed actions that resulted in the Medal of Honor. It was then-Lieutenant Colonel Smith who pushed the paperwork for the award through the Pentagon bureaucracy, a two-year process.

On the morning of April 4, 2003, the 11th Engineer Battalion of the Third Infantry Division broke through to Baghdad International Airport. With sporadic fighting all around, Smith’s men began to blow up captured ordnance that was blocking the runways. Nobody had slept, showered, or eaten much for weeks. In the midst of this mayhem, Smith got word that one of his platoon leaders, Sergeant First Class Paul Ray Smith (no relation) of Tampa, Florida, had been killed an hour earlier in a nearby firefight. Before he could react emotionally to the news, he was given another piece of information: that the 33-year-old sergeant had been hit while firing a .50- caliber heavy machine gun mounted on an armored personnel carrier. That was highly unusual, since it wasn’t Sergeant Smith’s job to fire the .50 cal. “That and other stray neurons of odd information about the incident started coming at me,” explains Colonel Smith. But there was no time then to follow up, for within hours they were off in support of another battalion that was about to be overrun. And a few days after that, other members of the platoon, who had witnessed Sergeant Smith’s last moments, were themselves killed.

Within a week the environment had changed, though. Baghdad had been secured, and the battalion enjoyed a respite that was crucial to the legacy of Sergeant First Class Paul Smith. Lieutenant Colonel Smith used the break to have one of his lieutenants get statements from everyone who was with Sergeant Smith at the time of his death. An astonishing story emerged.

Sergeant First Class Paul Ray Smith was the ultimate iron grunt, the kind of relentless, professional, noncommissioned officer that the all-volunteer, expeditionary American military has been quietly producing for four decades. “The American people provide broad, brand-management approval of the U.S. military,” notes Colonel Smith, “about how great it is, and how much they support it, but the public truly has no idea how skilled and experienced many of these troops are.”

Sergeant Smith had fought and served in Desert Storm, Bosnia, and Kosovo prior to Operation Iraqi Freedom. To his men, he was an intense, “infuriating, by-the-book taskmaster,” in the words of Alex Leary of The St. Petersburg Times, Sergeant Smith’s hometown newspaper. Long after other platoons were let off duty, Sergeant Smith would be drilling his men late into the night, checking the cleanliness of their rifle barrels with the Q-tips he carried in his pocket. During one inspection, he found a small screw missing from a soldier’s helmet. He called the platoon back to drill until 10 p.m. “He wasn’t an in-your-face type,” Colonel Smith told me, “just a methodical, hard-ass professional who had been in combat in Desert Storm, and took it as his personal responsibility to prepare his men for it.”

Sergeant Smith’s mind-set epitomized the Western philosophy on war: War is not a way of life, an interminable series of hit-and-run raids for the sake of vendetta and tribal honor, in societies built on blood and discord. War is awful, to be waged only as a last resort, and with terrific intensity, to elicit a desired outcome in the shortest possible time. Because Sergeant Smith took war seriously, he never let up on his men, and never forgot about them. In a letter to his parents before deploying to Iraq, he wrote,

There are two ways to come home, stepping off the plane and being carried off the plane. It doesn’t matter how I come home because I am prepared to give all that I am to ensure that all my boys make it home.

On what would turn out to be the last night of his life, Sergeant Smith elected to go without sleep. He let others rest inside the slow-moving vehicles that he was ground-guiding on foot through dark thickets of palm trees en route to the Baghdad airport. The next morning, that unfailing regard for the soldiers under his command came together with his consummate skill as a warrior, not in a single impulsive act, like jumping on a grenade (as incredibly brave as that is), but in a series of deliberate and ultimately fatal decisions.

Sergeant Smith was directing his platoon to lay concertina wire across the corner of a courtyard near the airport, in order to create a temporary holding area for Iraqi prisoners of war. Then he noticed Iraqi troops massing, armed with AK-47s, RPGs, and mortars. Soon, mortar fire had wounded three of his men—the crew of the platoon’s M113A3 armored personnel carrier. A hundred well-armed Iraqis were now firing on his 16-man platoon.

Sergeant Smith threw grenades and fired an AT-4, a bazooka-like anti-tank weapon. A Bradley fighting vehicle from another unit managed to hold off the Iraqis for a few minutes, but then inexplicably left (out of ammunition, it would later turn out). Sergeant Smith was now in his rights to withdraw his men from the courtyard. But he rejected that option because it would have threatened American soldiers who were manning a nearby road block and an aid station. Instead, he decided to climb atop the Vietnam-era armored personnel carrier whose crew had been wounded and man the .50- caliber machine gun himself. He asked Private Michael Seaman to go inside the vehicle, and to feed him a box of ammunition whenever the private heard the gun go silent.

Seaman, under Sergeant Smith’s direction, moved the armored personnel carrier back a few feet to widen Smith’s field of fire. Sergeant Smith was now completely exposed from the waist up, facing 100 Iraqis firing at him from three directions, including from inside a well-protected sentry post. He methodically raked them, from right to left and back. Three times his gun went silent and three times the private reloaded him, while Sergeant Smith sat exposed to withering fire. He succeeded in breaking the Iraqi attack, killing perhaps dozens of the enemy while going through 400 rounds of ammunition, before being shot in the head.

What impressed Colonel Smith about the incident was that no matter how many platoon members he solicited for statements, the story’s details never varied. Even when embedded journalists like Alex Leary and Michael Corkery of The Providence Journal-Bulletin investigated the incident, they came away with the same narrative.

After talking with another battalion commander and his brigade commander, Colonel Smith decided to recommend his sergeant for the Medal of Honor. He was now operating in unfamiliar territory. Standards for the Medal of Honor are vague, if not undefinable. Whereas the Medal of Honor, according to the regulations, is for “gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his or her life above and beyond the call of duty,” the Distinguished Service Cross, the next- highest decoration, is for an “act or acts of heroism … so notable” and involving “risk of life so extraordinary as to set the individual apart” from his comrades. There is no metric to differentiate between the two awards or, for that matter, to set the Distinguished Service Cross apart from the Silver Star. It is largely a matter of a commanding officer’s judgment.

Colonel Smith prepared the paperwork while surrounded by photos of Saddam Hussein in one of the Iraqi leader’s palaces. The process began with Army Form DA-638, the same form used to recommend someone for an Army Achievement Medal, the lowest peacetime award. The only difference was Colonel Smith’s note to “see attached.”

There are nine bureaucratic levels of processing for the Medal of Honor. Smith’s paperwork didn’t even make it past the first. Word came down from the headquarters of the Third Infantry Division that he needed a lot more documentation. Smith prepared a PowerPoint presentation, recorded the “bumper numbers” of all the vehicles involved, prodded surviving platoon members for more details, and built a whole “story book” around the incident. But at the third level, the Senior Army Decoration Board, that still wasn’t enough. The bureaucratic package was returned to Colonel Smith in December 2003. “Perhaps the Board had some sort of devil’s advocate, a former decorated soldier from Vietnam who was not completely convinced, either of the story or that it merited the medal.”

At this point, the Third Infantry Division was going to assign another officer to follow up on the paper trail. Colonel Smith knew that if that happened, the chances of Sergeant Smith getting the medal would die, since only someone from Sergeant Smith’s battalion would have the passion to battle the Army bureaucracy.

The Army was desperate for metrics. How many Iraqis exactly were killed? How many minutes exactly did the firefight last? The Army, in its own way, was not being unreasonable. As Colonel Smith told me, “Everyone wants to award a Medal of Honor. But everyone is even more concerned with worthiness, with getting it right.” There was a real fear that one unworthy medal would compromise the award, its aura, and its history. The bureaucratic part of the process is kept almost deliberately impossible, to see just how committed those recommending the award are: insufficient passion may indicate the award is unjustified.

“Nobody up top in the Army’s command is trying to find Medal of Honor winners to inspire the public with,” says Colonel Smith. “It’s the opposite. The whole thing is pushed up from the bottom to a skeptical higher command.”

Colonel Smith’s problem was that the platoon members were soldiers, not writers. To get more details from them, he drew up a list of questions and made them each write down the answers, which were then used to fill out the narrative. “Describe Sergeant Smith’s state of mind and understanding of the situation. Did you see him give instructions to another soldier? What were those instructions? When the mortar round hit the M113A3, where were you? What was Sergeant Smith’s reaction to it?”

“The answers came back in spades,” Colonel Smith told me. Suddenly he had a much fatter storybook to put into the application. He waited another year as the application made its way up to Personnel Command, Manpower and Reserve Affairs, the chief of the Army, the secretary of the Army, the secretary of defense, and the president. The queries kept coming. Only when it hit the level of the secretary of defense did Colonel Smith feel he could breathe easier.

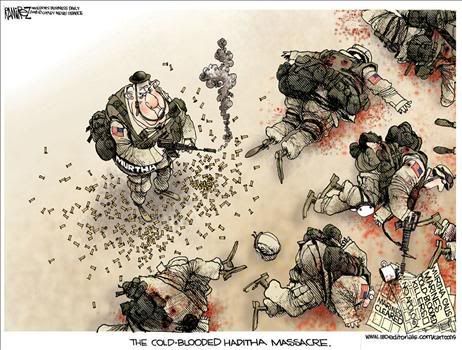

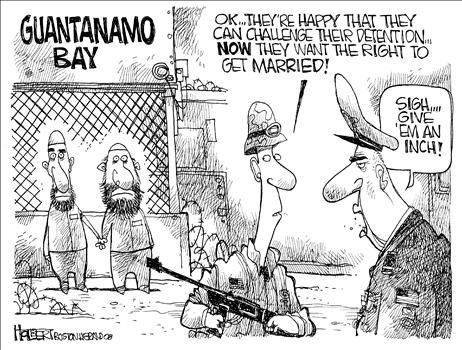

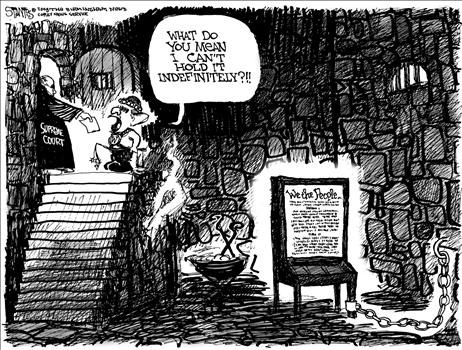

The ceremony in the East Room of the White House two years to the day after Sergeant Smith was killed, where President George W. Bush awarded the Medal of Honor to Sergeant Smith’s 11-year-old son, David, was fitfully covered by the media. The Paul Ray Smith story elicited 96 media mentions for the eight week period after the medal was awarded, compared with 4,677 for the supposed abuse of the Koran at Guantánamo Bay and 5,159 for the disgraced Abu Ghraib prison guard Lynndie England, over a much longer time frame that went on for many months. In a society that obsesses over reality-TV shows, gangster and war movies, and NFL quarterbacks, an authentic hero like Sergeant Smith flickers momentarily before the public consciousness.

It may be that the public, which still can’t get enough of World War II heroics, even as it feels guilty about its treatment of Vietnam veterans, simply can’t deliver up the requisite passion for honoring heroes from unpopular wars like Korea and Iraq. It may also be that, encouraged by the media, the public is more comfortable seeing our troops in Iraq as victims of a failed administration rather than as heroes in their own right. Such indifference to valor is another factor that separates an all-volunteer military from the public it defends. “The medal helps legitimize Iraq for them. World War II had its heroes, and now Iraq has its,” Colonel Smith told me, in his office overlooking the Mississippi River, in Memphis, where he now heads the district office of the Army Corps of Engineers.

Colonel Smith believes there are other Paul Smiths out there, both in their level of professionalism and in their commitment—each a product of an all-volunteer system now in its fourth decade. How many others have performed as valiantly as Sergeant Smith and not been recommended for the Medal of Honor? After all, had it not been for that brief respite in combat in the early days of the occupation of Baghdad, the process for the sergeant’s award might not have begun its slow, dogged, and ultimately successful climb up the chain of command.